5 Steps to Better Anticipation

Digital photography has reduced the anticipation of an image to mere milliseconds. We know almost instantly if our exposure was good or if anyone blinked or if we “got the shot.” Yet, with all of this immediate feedback, anticipation remains critical in photography. In the early 80’s, Heinz turned the irritation of their SMV (slow moving vehicle) ketchup into a moment of joyful anticipation – the joyful delay of a tasty pay-off.

Now, we have rapid image feedback from digital cameras and tethered monitors, but photographers can still find joy in things not-so-immediate.

Anticipation of composition

The viewfinder or monitor of your camera reflects a constant flux of changing elements, compositions and moments to select from. That photographic frame on the world might hold a banal array of random elements one moment and then a perfect confluence of harmony the next – and back to banal again in a breath.

Anticipation of composition is selecting the best moment when the graphic elements of lines, points, and shapes in the fore, mid, and backgrounds come together to direct the eye around the frame as you intend. This visual order of the elements may be symmetric, asymmetric, vertical, horizontal, or of some other organization, but the composition should always complement (complete) the subject.

Anticipation of the moment

Releasing the shutter places an indelible connection and correlation of elements and events in the frame to a specific time. Henri Cartier Bresson’s photographs powerfully demonstrate this connection by what he called the “decisive moment.”e It’s that moment in time when just one tick of the clock separates “The Moment” from “A Moment.”

The decisive moment demands the ability to predict the unfolding of a series of events. That sense comes only from experience.

Imagine you’re a sports photographer photographing basketball guard Chris Paul driving the lane on center Dwight Howard. As Paul nears the basket you anticipate a “stuff” or blocked shot. Your right index finger readies in expectation. Your time with the game, the teams, and the players directs your experienced eye to record the next series of moments.

It’s likely you already have a “double-wide palette” of experience from life. Let’s find out: Imagine you place a glass of milk near the edge of a table with a two-year-old running amok in the house. What do you anticipate happening? That the milk is living on borrowed time? There’s no need to camp out with your camera in hand waiting for this impending “decisive moment,” because with appropriate experience you can anticipate situation much less messy. This applies to any photography scene where objects and elements are constantly rearranging and moving around and in and out of your camera’s frame.

Not all “best” moments though happen within a given moment of time. Just being there at a moment in time is no guarantee that the “moment” was just waiting for us to show up.

Not all “best” moments though happen within a given moment of time. Just being there at a moment in time is no guarantee that the “moment” was just waiting for us to show up. When shooting outdoors, the weather and lighting can change, sometimes for the better if we are patient enough to wait-and-see. Anticipating change and how it might improve or even ruin a picture requires knowing what to look for and reapplying it at a later time. Below, the swing and hedge photos show the difference a day can make.

Anticipation of Loss of Depth

Experience of change is not limited to the world around us - change also operates within the frame of our camera. Viewing the world through our camera is the experience that helps us recognize how photography takes our three-dimensional world and reduces it to only two dimensions of height and width. We have lost the dimension of depth. In order to recover it, we need to understand the illusion of how we perceive depth in a two-dimensional space.

On a recent trip to the Oregon coast, we saw amazing scenery from Highway 101 and decided to hike down to get a closer look. The photo below shows the fog starting to roll in on a warm January’s afternoon. The problem with the picture is the lack of depth. The similar gray values give it a rather flat, dimensionless appearance.

Drawing on years of seeing the world through a viewfinder, I anticipated the need for more depth. I turned the camera vertically and tipped it down revealing darker rocks in the foreground. The dark to light value change indicated an aerial perspective meaning distance in the scene. This change in scene value translates easily to perceived dimension in a photograph. There is also a curving vertical line formed by the rocks and an ocean wave drawing the eye up the photo. The viewer perceives moving deeper into the picture rather than simply up the frame. Shooting wide angle (18mm on an APS-C sensor) also helped to increase the feeling of depth by emphasizing the foreground elements.

Anticipation of equipment

Knowing your camera gear may be even more important than knowing the best moment. If you sense that an important moment is about to happen and you’re making adjustments to your ISO, but can’t remember how to access it, you probably just lost the shot. Shutter speeds, apertures and ISO’s can help define the “look” of your photo.

- Caveat Emptor – There is a difference in camera gear out there. Some point and shoot and cell phone cameras have enough of a shutter lag and delay that it may cause you to miss your shot. Best advice - anticipate your gear.

If however, you only use the Easy Green Auto exposure control and find yourself with a backlit scene, you may risk loosing a picture because you couldn’t remember which wheel controlled your exposure adjustment.

Know the locations and functions of all those buttons on your camera to help your hands function more effectively, but knowing the visual results of those exposure changes gives you access to a visual mother load of creative approaches with your subject.

You may be thinking, “That sounds nice, but how do those exposure controls affect the photo?” Let’s try and tie them into anticipation. The shutter controls motion. This means you would anticipate some shutter speed to either freeze motion (using a fast shutter seed) or blur motion (using a slow shutter speed).

The aperture controls the amount of sharpness from the front to the back of the scene you are shooting. The higher the f-stop, the more depth of focus you will have in the photo. Lower f-stop numbers are good for isolating the subject from the background as the photo below shows.

Anticipation by way of Curiosity

Anticipation driven by curiosity happens when you experiment with your camera gear and it starts with the question “What if?” What if I moved in really tight on my subject? What would it look like if I used a really slow shutter speed on this fast moving subject. What if I used a different white balance other than “Auto?” By employing this cause and effect question, you will create a natural learning process of “attempt – succeed/fail – gain experience.” And, just like that you’re on the road to anticipating beautiful pictures.

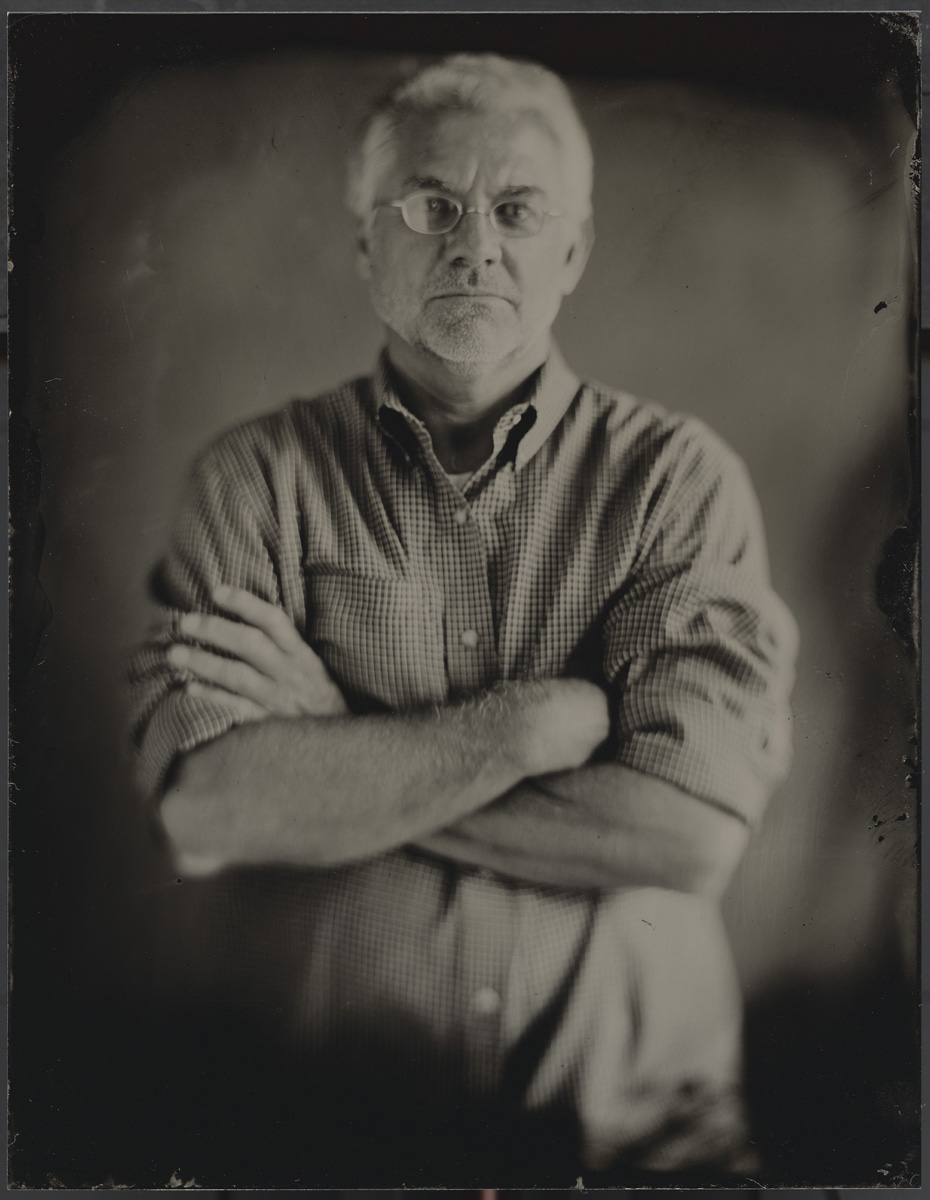

For the better part of three decades, Roger Tuttle has photographed life, for pay and for passion. Along with his varied photo projects, Roger splits time teaching Photography at the University of Utah and Utah Valley University.

His primary shooter is a Vivitar 600 (not really).